Parasitic Architecture: A Wall Divides 分裂墙之传

June 2020

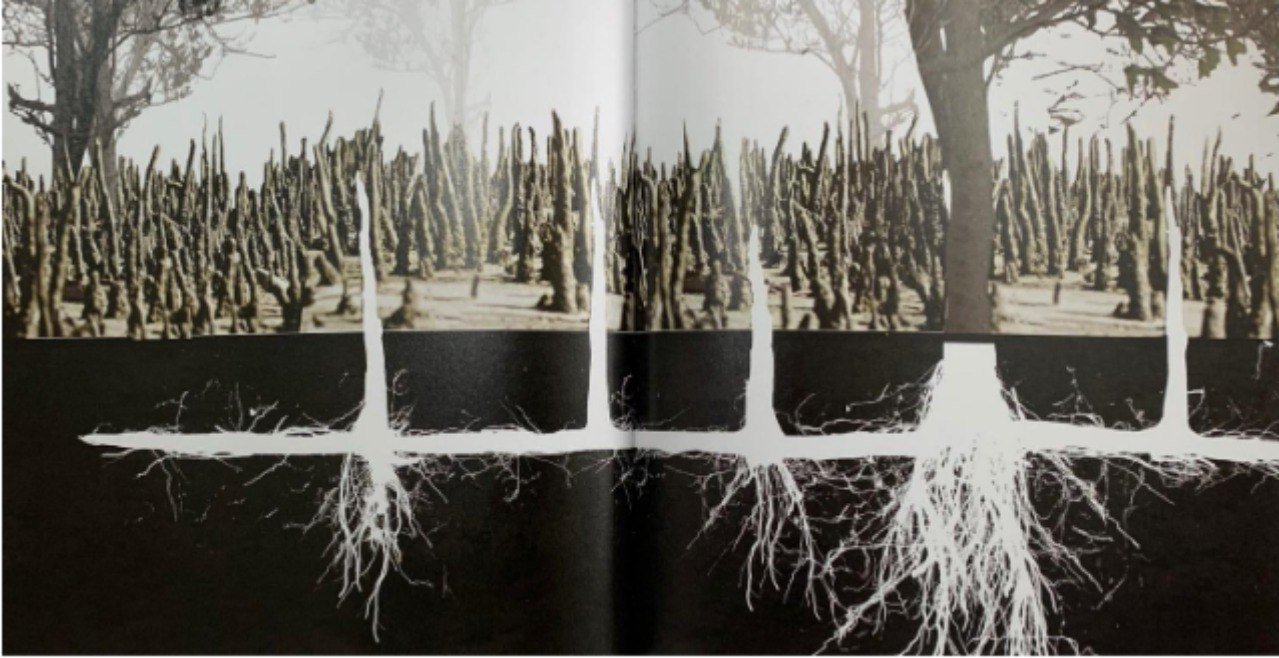

Image credits to: Diana Agrest Architecture of Nature: Nature of Architecture

City walls form a barrier of protection for inhabitants from threats from beyond since early civilization. Entry into the city is through the city gates. In the present day, these gates are the ports of call – airport, seaport, and border crossing. They are perceptible barriers for the purpose of screening nonresidents coming into the city. However, there exists powerful invisible barriers within a city as well. They define precincts for specific functions, and segregate those who have and those who have not. There are psychological barriers: unseen but marked territorial boundaries, non-physical boundary walls. If these invisible walls could speak, they would share tales of envy, desire, despair, emptiness, anger, jealousy, helplessness, evil, injustice, arrogance, pretentiousness, and ignorance. But they would also share stories of pride, motivation, kindness, empathy, negotiation, and accommodation.

The issue on the right of access to city spaces is a long-standing topic in social geography. Social spatial equity is located at a peripheral position in mainstream social discourse, planning and architecture; treated like a neglected child that is only occasionally showered with some attention and care. While the rights to access to public outdoor spaces may be available, there are coded barriers to the enjoyment of these spaces and public amenities. Obstacles often cited are the lack of public funding or a commercially driven mindset that public amenities should be self-funding towards the cost, management, and maintenance of infrastructure, for example Gardens by the Bay or Marina Bay. While this may seem perfectly understandable, it has also shifted design emphasis to profit instead of promoting public wellness.

Unsurprisingly, the programmes and activities are catered to tourists. Likewise, the planning and architectural design orientation of ‘public outdoor spaces in the city’ puts the interests of city residents below that of the tourists. Within city residents, there are also tiers of affordability. The unwritten code that users should pay for the enjoyment of public spaces and amenities underscore urban planning and architecture design parameters in the city. Perhaps it unintentionally accentuates a community divide.

The Covid 19 pandemic has changed all these game plans. There is an awakening of the social responsibility in the community and a political price for ignoring social spatial inequity. The forms and functions of caring social spaces have become the subject of interest among politicians, academics and the community. We hope that talking the talk would also mean walking the walk.

Amidst the conversation, density has found itself to have become a dirty word. Choruses of ‘less density’, ‘less crowdedness’, ‘social distancing’ are the new battle cries. But is it true that high density is bad, and low density is good? Perhaps another oversimplification. Intensification of land use i.e. density does not naturally lead to crowdedness. The focus should be on the manner and frequency of use in a day i.e. 24 hours. Diversity in urban design and multiple programmes in architectural design can optimize land use. More importantly, these facilities are used by diverse user types and demographics. There is no reason why public amenities cannot be replicated in smaller scales across the city. This will consequently achieve less crowdedness, yet still permitting higher usage by all residents in the community over a day. This is the proposition that should motivate planners and architects seeking a socially equitable urban design and architecture.